VANCOUVER — Beneath the glacier-scoured lakes and barren tundra of the Northwest Territories (N.W.T.) and Nunavut is a collection of disparate Archean- to Proterozoic-aged crust that were stitched together along vast mountain ranges during the assembly of ancestral North America 2 billion years ago.

These major blocks include the Wopmay orogen in the west and the Slave, Rae and Hearne cratons in the east, whereas rocks impacted by the Trans-Hudson and Innuitian orogens are found in the east and far north.

For millions of years, oceans and extensive seaways blanketed parts of the ancient continent with sediments derived from the mountains between the cratons eroding down to their core.

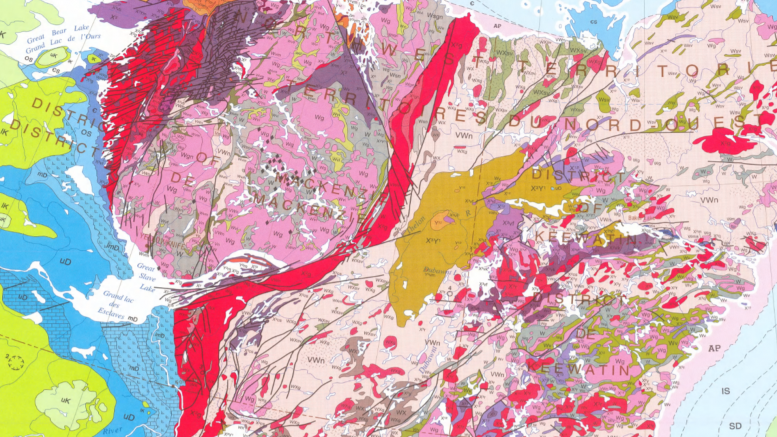

The geological framework of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Credit: Geological Survey of Canada/Lesley Stokes.

The geological framework of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Credit: Geological Survey of Canada/Lesley Stokes.

The Mackenzie Mountains hold 55% of the world’s known reserves of tungsten and significant reserves of lead-zinc, with major deposits including the skarn-related Cantung tungsten deposit and Canadian Zinc’s (TSX: CZN; US-OTC: CZICF) Mississippi Valley Type (MVT) Prairie Creek deposit in the Northwest Territories, and Selwyn-Chihong Mining’s sedimentary-exhalative (Sedex) Howard’s Pass zinc-lead deposit on the border.

Proterozoic-aged sedimentary-hosted copper deposits — like those found in the Zambian and Congolese copper belts — are also seen in the Mackenzie Mountains, notably Copper North Mining’s (TSXV: COL) Redstone copper deposit in the Northwest Territories.

A plethora of other deposit types are scattered across the N.W.T. and Nunavut, confined to the geological boundaries of the cratons that host them. These deposits include iron-oxide copper-gold (IOCG); diamond-bearing kimberlites; orogenic and banded-iron formation (BIF) hosted gold; basement and unconformity-hosted uranium; magmatic nickel-copper; and MVT lead-zinc, to name a few. Substantial reserves of oil and gas are also available in the N.W.T., occurring within deep sedimentary basins similar to Alberta.

Modern explorers rely on geological maps to home in on prospective targets, but the lack of access into parts of Canada’s North has prevented government and industry geologists from mapping the region in much detail. With many regions left untouched by hand or hammer, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories have earned their reputation as the last frontier for exploration in Canada.

Select deposits, districts and geology in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Credit: Geological Survey of Canada/Lesley Stokes. A more detailed version of Canada’s geological map and legend can be downloaded here.

Select deposits, districts and geology in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Credit: Geological Survey of Canada/Lesley Stokes. A more detailed version of Canada’s geological map and legend can be downloaded here.

Wopmay orogen: IOCG

During the assembly of ancestral North America, metamorphosed crust belonging to the Hottah terrane in the N.W.T. collided with the Slave craton, an Archean-aged package of weakly metamorphosed, volcano-sedimentary terranes called greenstone belts.

The collision triggered subduction along the western margin of the Hottah, and fractures and faults were injected with granitic magmas, locally enriched with uranium or exploited by gold-bismuth-cobalt-copper-rich fluids driven by underlying IOCG systems.

This mineral-rich tectonic margin, known as the Great Bear magmatic zone, hosts the historic Port Radium uranium-silver mine and Fortune Minerals’ (TSX: FT) Nico deposit, the latter hosting 33 million tonnes of 1.03 grams gold per tonne, 0.11% cobalt, 0.14% bismuth and 0.04% copper. The combined rock package is called the Wopmay orogen.

Slave craton: Diamonds

The accretion of the Bear thickened the crust underneath Slave, and the combined rock package lengthened to a depth where immense pressures transformed carbon-rich material into diamonds.

The diamonds remained undisturbed until 55 million years ago, when volatile, rich magmas drove up through the crust, moving the precious stones to surface. These diamond-bearing kimberlites were later uncovered by explorers in the Lac de Gras region of the N.W.T., most notably at Dominion Diamond (TSX: DDC; NYSE: DDC) and Rio Tinto’s (NYSE: RIO; LON: RIO) Diavik, Dominion’s Ekati and De Beers’ Gahcho Kué diamond mines. Farther north, the former Jericho diamond mine is hosted within Nunavut’s portion of the Slave, whereas the most advanced exploration project in the region is Kennady Diamonds’ (TSXV: KDI; US-OTC: KDIAF) Kennady North, located 5 km from the Gahcho Kué mine in the Northwest Territories.

Gold

While diamonds attract the most attention in the N.W.T., gold has also lured explorers into Canada’s northern latitudes. The greenstone belts that occupy the Slave craton are similar, if not identical, to those of the Superior craton in the gold-prolific regions of Ontario and Quebec, but are relatively unexplored.

Most of the gold exploration work in the Slave craton has focused on the Yellowknife Gold greenstone belt, which hosts the historic 7.6 million oz. Con and 5.5 million oz. Giant gold mines, located outside the capital city of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories.

TerraX Minerals (TSXV: TXR) is exploring the rest of the belt at its Yellowknife City Gold project, whereas 200 km north, Nighthawk Gold (TSXV: NHK) is uncovering a gold-rich greenstone belt at its Colomac property.

In Nunavut’s portion of the Slave craton, north of N.W.T., major gold projects include TMAC Resources’ (TSX: TMR) 4.5 million oz. gold Hope Bay project and Sabina Gold & Silver’s (TSX: SBB; US-OTC: SGSVF) 5.3 million oz. gold Back River project. WPC Resources (TSXV: WPQ) is also working to restart operations at the shuttered Lupin gold mine, which produced 3.4 million oz. gold at average grades of 8.9 grams gold before closing in 2005. (Both Lupin and Back River are Archean-aged, BIF-hosted gold deposits, whereas the rest are Archean orogenic, lode gold systems.)

While most explorers focus on gold and diamonds in the Slave, volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) base-metal deposits are also known to occur, such as Glencore Canada’s Hackett River in Nunavut. The deposit contains 25 million indicated tonnes of 4.2% zinc and 130 grams silver per tonne, and 57 million inferred tonnes of 3% zinc and 100 grams silver.

A view of the airstrip at the Colomac project, part of Nighthawk Gold’s Indin Lake gold property in the Northwest Territories 220 km north of Yellowknife. Photo by Nighthawk Gold

Churchill province, Rae-Hearne cratons

The eastern side of Slave is sutured against the Churchill province, a geological domain divided into two cratons: Rae and Hearne. Rae and Hearne are separated by the enigmatic, 1.9-billion-year-old Snowbird tectonic zone, which stretches northeast for 2,800 km from the Canadian Cordillera, before disappearing beneath Hudson Bay.

Geologists believe that the Rae-Hearne cratons are geologically similar to the Slave craton — being composed of a mix of greenstone belts and intrusives — but are slightly younger in age, and covered more extensively with Proterozoic-aged sedimentary rocks.

Because of its remoteness, little is known about Churchill, and many of its geological boundaries are still being refined.

Gold

The Rae craton is more deformed than the Hearne, having been hit repeatedly on both sides by cratons from 2.6 billion to 1.9 billion years ago. These events intensely metamorphosed parts of the crust, and any pre-existing metal deposits that are common in greenstone belts — such as orogenic gold or VMS deposits — would have been obliterated by the immense pressures and temperatures.

Most of the known gold occurrences in the Churchill occurred during the waning stages of deformation related to the Trans-Hudson orogen, 1.9 to 1.8 billion years ago — almost 1 billion years after the main gold mineralizing events in the Slave or Superior craton.

In this younger event, gold-rich fluids — drawn from the partial melting of crust during metamorphism, or remobilized from older deposits — circulated through structures until it found chemical traps, such as BIF, and deposited the metals.

The most significant examples of Proterozoic-aged, BIF-hosted gold deposits are found where the Snowbird slices through the Rae craton. These deposits include Agnico Eagle Mines’ (TSX: AEM; NYSE: AEM) 3.5 million oz. Meadowbank mine in south-central Nunavut, its 3.7 million oz. Amaruq exploration project, 55 km north of Meadowbank, and its 3.4 million oz. Meliadine deposit in southeastern Nunavut.

Aside from Amaruq, the most advanced exploration project in the Rae craton is Auryn Resources’ (TSX: AUG; US-OTC: GGTCF) Committee Bay, 180 km northeast of Meadowbank. The project occurs within a weakly metamorphosed section of the 300 km long Committee Bay greenstone belt, home to the 1.3 million oz. gold Three Bluffs BIF-hosted deposit.

Compared to the Rae craton, Hearn hosts few known gold occurrences, despite its greenstone belts being well-preserved and sheltered from intense metamorphism.

Nordgold’s (LON: NORD) Pistol Bay project along the coast in southern Nunavut is the most advanced project in the Hearne craton, with 739,000 oz. gold at 2.95 grams gold being noted in resources. The project falls within the Rankin-Ennadai greenstone belt, which also hosts the historic North Rankin Inlet magmatic nickel-copper deposit. North Rankin Inlet produced 500,000 tonnes of ore at grades of 3.3% nickel and 2.8% copper, before shutting down in 1962.

Workers at a drill on Agnico Eagle Mines’ Amaruq gold property in Nunavut. Credit: Agnico Eagle Mines.

Workers at a drill on Agnico Eagle Mines’ Amaruq gold property in Nunavut. Credit: Agnico Eagle Mines.

Uranium

Once the Trans-Hudson orogen came to a halt, sediments eroded off the mountain peaks and deposited into deep basins, preserved today as the Athabasca basin in Saskatchewan and the Thelon basin that spans the N.W.T. and Nunavut border. The basins are both underlain by the Snowbird tectonic zone, which acted as a conduit for uranium-rich fluids 1.5 billion years ago. The structures, and where they pierce the overlying sediments, served as favourable traps for basement- and unconformity-hosted uranium deposits.

In the Athabasca, explorers have uncovered a number of world-class uranium deposits, and those that have been converted into mines account for 20% of global uranium supply. The same opportunity of scale exists in the Thelon basin, with Areva’s 134 million lb. U3O8 Kiggavik project in Nunavut’s portion of the basin as being proof-of-concept, but exploration in the region has been limited owing to local and governmental opposition.

Iron

The northern part of Nunavut’s Baffin Island is home to one of the highest-grade iron mines in the world: Baffinland Iron Mines’ Mary River. The deposit occurs within a highly metamorphosed segment of the Committee Bay greenstone belt, and contains reserves of 365 million tonnes of 65% iron.

Trans-Hudson orogen

Baffin Island is divided into two segments: the Rae craton in the north, and exotic terranes impacted by the Trans-Hudson orogen in the south. While iron dominates exploration in the north, diamonds and magmatic nickel-copper deposits are the prize for explorers in the south.

Diamonds

Peregrine Diamonds (TSX: PGD) was the first explorer to uncover diamond-bearing kimberlites in Baffin Island at its Chidliak project in 2008. The kimberlites jut through an undeformed block of Archean crust entangled within the Trans-Hudson orogen. The kimberlites contain 9.6 million inferred tonnes of 1.57 carats per tonne.

Canada’s Baffin Island near the Chidliak site. Credit: Peregrine Diamonds.

Magmatic nickel-copper

Baffin Island’s share of the Trans-Hudson orogen could host magmatic nickel-copper deposits, such as those seen within the Ungava trough’s Raglan mining camp in northern Quebec (formerly known as Cape Smith belt), and the Thompson nickel belt in Manitoba.

Both of the world-class mining camps were formed when the Superior craton rifted open during the Trans-Hudson orogeny, which in turn created sedimentary platforms that were injected with nickel-copper rich ultramafic intrusions and lava flows. Similar environments could occur within Nunavut’s portion of the Trans-Hudson orogeny.

Innuitian orogen and Paleozoic-Mesozoic sedimentary cover rocks: Lead-zinc

Shallow seas inundated the lowlands up until 70 million years ago, and blankets of carbonates, shales and sandstones were deposited both across the continent and along its margins. The seas diminished when outboard volcanic terranes in the west accreted onto the landmass during the assembly of B.C. and the Yukon.

The tectonic environment fostered the growth of Sedex lead-zinc deposits such as Howard’s Pass, whereas the carbonate rocks served as a perfect environment for MVT lead-zinc deposits. MVT deposits form when mineralizing brines flush along basin-bounding faults into structurally prepared cavities created by the dissolution of carbonates.

Two of the main MVT deposits in Nunavut and the N.W.T. — Polaris and Pine Point, — formed 360 million years ago, when immense pressures during the Innuitian orogen squeezed metal-rich fluids out of shales and into the carbonates.

Polaris and Pine Point are considered world-class deposits, with production reaching 21.5 million tonnes of 4% lead and 7.2% zinc over a 21-year mine life at Pine Point, whereas production at Polaris topped 21 million tonnes of 14% zinc and 4% lead over its 20-year mine life. At the time of production, Polaris was the northernmost mine in the world.

Most of the exploration for base metals in the north are confined to projects along the coastline, as access to seaports are perceived as vital for a project’s economic success. While exploration for MVT deposits is limited, junior explorer Darnley Bay Resources (TSXV: DBL) is working to renew exploration at Pine Point.

An aerial view of two historic open pits mined by Cominco, at Darnley Bay Resources’ Pine Point zinc project in the Northwest Territories. Credit: Darnley Bay Resources.

Be the first to comment on "There’s more than meets the eye in NWT and Nunavut"